EAGLE SYNDROME

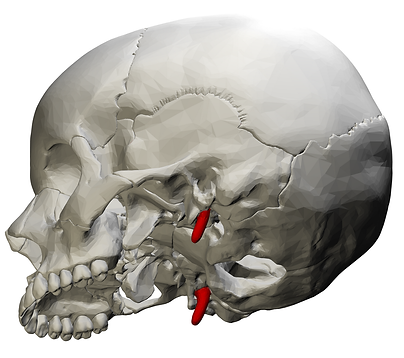

Eagle Syndrome is a condition where an elongated styloid process or calcified stylohyoid ligament in the neck causes compression or irritation of nearby nerves or blood vessels, leading to a range of head, neck, face, or vascular symptoms.

ANATOMY

What’s the Styloid Process?

-

A thin, pointed bone located just below your ear.

-

Normally around 2.5–3 cm long.

-

In Eagle Syndrome, it’s often >3 cm and can press on:

-

Cranial nerves (like glossopharyngeal, trigeminal, or vagus)

-

Internal carotid artery

-

Internal jugular vein

-

TYPES

There are two types of eagles syndrome

-

Classic Eagle Syndrome: Nerve compression (often CN IX)

-

Vascular Eagle Syndrome: Compression of artery or vein

Polygon data were generated by Database Center for Life Science(DBCLS)[2]. CC-BY-SA-2.1-jp

SYMPTOMS

Classic (nerve-related):

-

Throat or ear pain

-

Pain with swallowing, turning the head, or yawning

-

Sensation of a foreign object in the throat

-

Jaw or facial pain

-

Voice changes

Vascular (vein or artery compression):

-

Head pressure (especially when lying down or turning head)

-

Dizziness or lightheadedness

-

Pulsatile tinnitus (hearing your heartbeat in your ear)

-

Visual disturbances

-

Stroke-like symptoms (rare but serious)

-

Often linked with internal jugular vein compression → increased intracranial pressure leading to a condition called Intracranial hypertension

Symptoms can fluctuate depending on head position — turning or tilting can worsen or relieve compression.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Anatomy

-

The styloid process is a slender bone extending from the temporal bone of the skull, normally about 2–3 cm long.

-

When elongated (often > 3 cm) or abnormally angled, it can impinge on nearby neurovascular structures.

-

The stylohyoid ligament, connecting the styloid process to the hyoid bone, can also become ossified, acting like an extra bony bar in the neck.

-

Eagle Syndrome typically manifests in two overlapping forms, each with distinct mechanisms.

Vascular (Stylocarotid or Stylojugular Type)

-

The elongated styloid process or calcified ligament compresses blood vessels, particularly:

-

The internal carotid artery (ICA)

-

The external carotid artery (ECA)

-

The internal jugular vein (IJV) (between the styloid process and the C1 transverse process)

-

-

Compression can lead to:

-

Arterial irritation or dissection → transient ischemic attacks (rare)

-

Venous outflow obstruction → increased intracranial pressure, headache, visual symptoms, tinnitus, cognitive fog

-

-

This venous subtype is sometimes called “Styloidogenic Jugular Venous Compression Syndrome.”

Mechanism:

Mechanical narrowing → turbulent or reduced blood flow → venous hypertension → secondary intracranial hypertension symptoms.

Neurological (Classic Eagle Syndrome)

-

The styloid process or ossified ligament compresses or irritates nearby cranial nerves, particularly:

-

Glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) – throat and tongue pain

-

Vagus nerve (CN X) – voice changes, autonomic symptoms

-

Trigeminal nerve branches – facial pain or jaw discomfort

-

Facial nerve (CN VII) – sometimes causes ear pain

-

Mechanism:

Mechanical irritation or compression → local inflammation and neuropathic pain → referred pain to the throat, ear, or jaw.

Positional Effects

-

Turning or tilting the head can worsen compression — particularly of the internal jugular vein — explaining positional headaches or pulsatile tinnitus.

-

Some patients develop dynamic compression seen only when the neck is rotated or extended on imaging (CT or MR venography).

DIAGNOSIS

Usually involves imaging to measure the length and position of the styloid process and look for vascular or nerve compression

-

CT scan with 3D reconstruction is the gold standard (best to measure styloid)

-

CT Venography or Angiography (CTV/CTA) – shows vascular compression

-

Ultrasound or Doppler – for blood flow evaluation

-

Dynamic rotational venography - shows how neck position changes venous outflow.

-

MRV (Magnetic Resonance Venography) and cone-beam CT - provides less radiation

TREATMENT

Conservative management

Management of pain and symptoms with medication

Steroid or lidocaine injections around the styloid for diagnostic or temporary relief

Physical therapy or posture correction in milder cases

This approaches may relieve pain but don’t fix the structural problem (elongated styloid or compressed vein/artery).

Surgical Treatment – Styloidectomy

This is the definitive treatment for most symptomatic cases.

-

Removal or shortening of the elongated styloid process

-

May be combined with removal of calcified stylohyoid ligament

Two Surgical Approaches:

-

Intraoral: Through the mouth (tonsillar area). No external scar, but less visibility

-

External: Small incision in the neck. Better visibility, safer for vascular cases, leaves scar

-

Recovery time: 2–6 weeks

-

Usually done under general anesthesia

-

Low complication rate with experienced surgeons

If Jugular Vein or Artery Is Compressed

In vascular Eagle Syndrome, you may also need:

-

C1 bone shave: C1 vertebra is also compressing the jugular vein

-

Venous stenting: Vein remains narrowed even after bone removal

-

Carotid artery decompression: If the elongated styloid presses on the carotid artery (rare)

Complications

-

The styloid process lies close to several cranial nerves — these can be stretched, irritated, or injured during surgery.

-

Temporary soreness or tightness when swallowing is common. Rarely, pharyngeal scarring or dysphagia can persist, especially after intraoral approaches.

-

Persistent or recurrent pain (if part of the styloid remains or scar tissue forms)

-

Incomplete symptom relief (especially if venous compression is from multiple causes, e.g., C1 vertebra or ligament)

-

Scar tissue or fibrosis causing tightness in neck muscles

-

In rare cases, symptoms may recur if the styloid regrows or calcification continues.

Picture showing measurement made on an elongated styloid

PRE-SURGERY CONSIDERATIONS

In vascular Eagle Syndrome, the elongated styloid process or calcified ligament can compress major blood vessels, most often the internal jugular vein (IJV) or, less commonly, the internal carotid artery (ICA).

Before any surgical removal (styloidectomy), it’s crucial to determine exactly where and how the compression occurs. This matters because:

-

Multiple structures can contribute to the narrowing. Sometimes it’s not just the styloid, the C1 vertebra (atlas) can also press against the vein. If only the styloid is removed and the C1 bone continues to pinch the vein, the symptoms such as head pressure, tinnitus, or dizziness may persist or return.

-

Targeted surgery prevents incomplete relief. By performing pre-operative venography or dynamic imaging, surgeons can decide if the patient also needs a C1 bone shave to free up the jugular vein, or in some cases, a venous stent after surgery if the vein remains narrowed.

-

It reduces surgical risk. Knowing which vessels are involved helps surgeons plan a safer surgical route and avoid complications related to nearby nerves and arteries.

-

It distinguishes nerve-related from vascular symptoms. Classic (nerve-type) Eagle’s and vascular Eagle’s can overlap in symptoms, and detailed vascular evaluation helps confirm which mechanisms are at play so treatment can be tailored correctly.

In short, proper vascular imaging before surgery ensures the real cause of compression is identified, the right structures are addressed, and unnecessary or incomplete surgeries are avoided.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis for Eagle Syndrome is generally good, especially when appropriate treatment is provided. Most patients experience partial to full relief of symptoms after treatment — particularly after surgical intervention.